Stigma and Stigmata

I’ve always had a fascination with the stigmata.

If you’re not Catholic, you may not be familiar with this Greek word, which can be translated “wound” or “mark.” It typically refers to the wounds that Jesus received on the Cross: the nail marks in his hands and feet, the wound where the soldier’s sword pierced his torso, and sometimes including the crown of thorns on his head.

There are several saints throughout history that have, through supernatural means, received the stigmata as a grace to be uniquely united to Jesus’ salvific action on the Cross.

Padre Pio is probably the most recent saint to have the stigmata. He was investigated thoroughly to make sure they were not self-inflicted and did not have any natural explanation. While you might expect open wounds like he had to have quite an odor, it was reported that his hands smelled like roses.

Other saints that experienced the stigmata include St. Francis of Assisi, St. Catherine of Siena, and St. Gemma Galgani.

I first learned about Padre Pio, an Italian Franciscan friar, from a holy card that my mom had stuffed into her visor in the car. The card had been a gift and my mom didn’t know much about him, so I researched his story.

When most people think about saints, they think about heroic acts of charity. They think about Mother Teresa serving in the slums, St. Maximillian Kolbe giving up his life at Auschwitz so that a Jewish father could live, or St. Frances Cabrini living in squalor to serve the Italian immigrants to New York City.

I’ve always been attracted to a different aspect of the lives of the saints, though, a disposition that God gave me with the knowledge of what I would experience. I’ve always been attracted to the way the saints have conformed their lives to the crucified Christ. Specifically, the way the saints seem utterly unbothered by suffering, undergoing it sometimes even with joy.

“Stigmata” has the same root as a word that is much more common: stigma. Stigma is a mark, like a scarlet letter, which sets someone apart to be the scapegoat for society’s shame and disgrace.

Now, I could write about stigma for thousands of words, and it will likely be a good portion of the book that I’m currently working on. But I thought I would give a high-level overview of my personal spirituality as someone who experiences mental illness, which is based entirely on the word “stigmata.”

In his letter to the Galatians, St. Paul writes, “From now on, let no one make troubles for me; for I bear the marks of Jesus on my body.” (Gal. 6:17)

The actual Greek word that St. Paul uses is, you guessed it: stigmata.

Now, there are a few interpretations of St. Paul’s use of the word. Perhaps, like future saints, he actually had received the wounds of Christ through supernatural means. He also could be making a comparison, saying that he is united to Jesus in his suffering in prison.

Like many people who experience mental illness, I have engaged in self-harm in the past. Praise God, it has been several years since , but it is still something that carries a great deal of shame for me. I still have the marks on my arm. I still carry the stigmata.

While I do have external wounds, they are merely the result of the internal wounds that I bear. There is a great deal of shame I have around those wounds as well. I carry the sense that I should just get over them, that I’m still hurting because of a hard, unforgiving heart. I carry a sense that I am used up, that my mental illness will preclude me from ever fulfilling a vocation, keeping me from getting married just like it kept me from becoming a religious sister.

I carry the stigma. I carry the stigmata.

But just like Jesus’ wounds, these wounds will not be in vain. Remember, St. Paul said that no one can trouble him because he had the stigmata. Because he bore the wounds of Christ.

It is in these deep places that we come not only to know Jesus, but to be transformed into Him. We, who are made in His image and likeness, marred by sin, are restored because we know that sin and death do not have the last word. To be conformed to Jesus Christ in his suffering, offering our suffering along with His for the salvation of the world, is to also have life in Him through His Resurrection.

Now, to be clear, suffering is an evil. Suffering does not de facto help us know Jesus. It is a grace, a gift of our good, good God, that he allows this evil to bring about something even better than what could have existed without it.

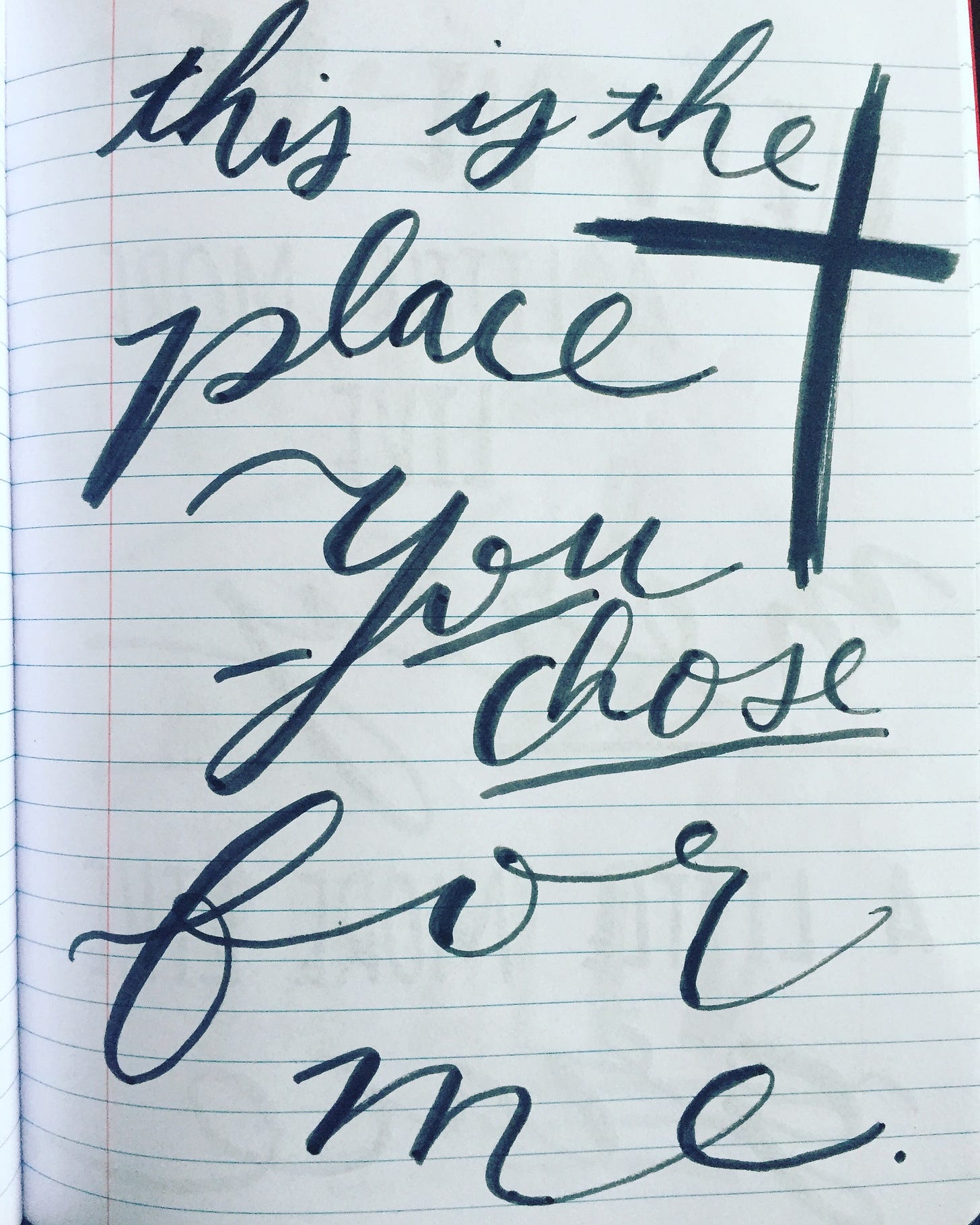

A couple years ago, I got a cross tattoo on my wrist. It’s a lopsided cross, a replica of a cross that I drew in my journal at one of the darkest points of my life. I love it, as I usually have my sleeves rolled up and it is visual at all times.

It reminds me that no one can make troubles for me, for I bear the marks of Jesus on my body.

I want to say thank you to the paid subscribers to this newsletter, which I originally started . Thank you to those who have joined since I re-launched it, as well as those who have supported it from the beginning and even when I wasn’t writing at all. I’m grateful for your support, and knowing that you are reading my silly little reflections keeps me coming back to write more.

If you’re not a paid subscriber, thank you for reading this far. I’m using these newsletters to work out some of the ideas for my next book.

If you find this newsletter to be of value, I hope you will share it. If you feel moved to support it financially as well, I would be most grateful. If you’d like to send a one-time gift of support, you can do that through PayPal and I’ll add your email to the paid subscriber list.

Paid subscribers receive an unhinged media review every Friday. Last week I reviewed Conclave, the week before I reflected on holding space for “Defying Gravity.” This week I’ll be sharing some thoughts on Cloistered, a memoir I just finished of a woman who left a cloistered convent after 12 years.